Cultural treasure rambles

Enjoying Classic Paintings and Craft Objects (Kita-Kamakura Station area)

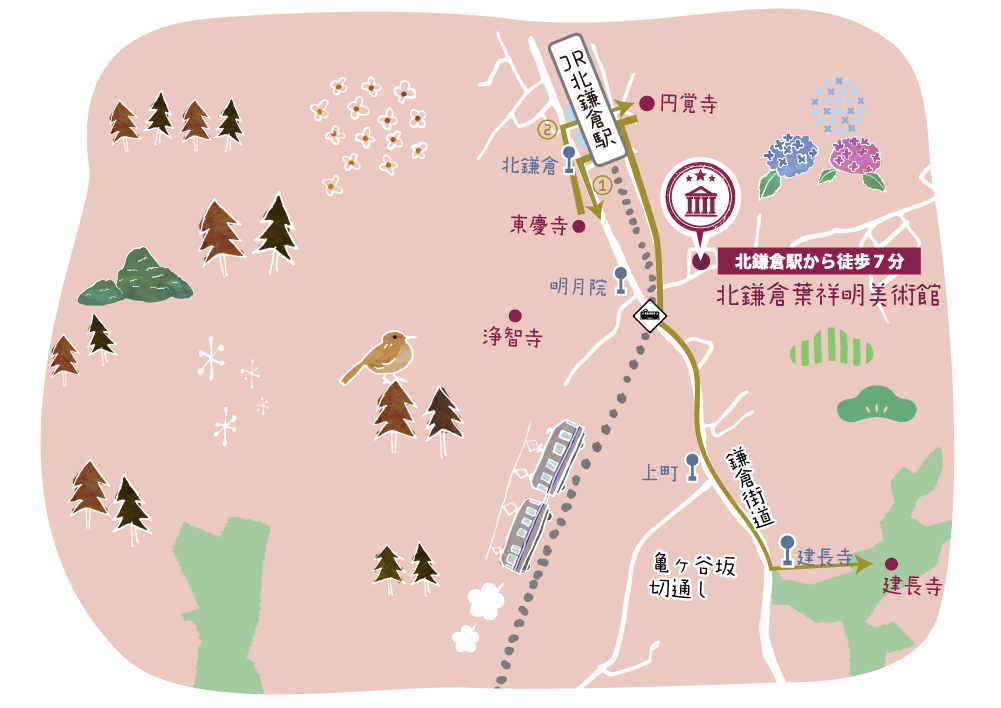

- Kita-Kamakura Station

- 4 minutes-walk

- Tokeiji Temple①

Hatsune Maki-e Hitorimo - Tokeiji Temple②

Pyx Decorated with Grape Motifs in Maki-e and Mother-of-Pearl Inlay - Tokeiji Temple③

Inkstone Case with Wave and Hexagonal Motifs in Maki-e - Tokeiji Temple④

Priest’s Brush with Peony and Arabesque Motifs in Maki-e - Tokeiji Temple⑤

The Matsugaoka Journal- 3 minutes-walk

- Engakuji Temple

- 10 minutes-walk

- Kenchoji Temple

- 16 minutes-walk

- Kita-Kamakura Station

Kita-Kamakura Station Start

Kita-Kamakura Station Start

The temples in Kita-Kamakura are treasure houses of rare cultural properties. Touring them while imagining how people lived back in those days—doesn’t that sound fascinating?

A poem from the Tale of Genji inspired its design.

A hitori is an incense burner used to impregnate clothing with the aromas of incense. The body of this piece has a nashi-ji (pear-skin) ground. In that type of maki-e lacquer, fine flakes of gold or silver are scattered on the surface of the piece and coated with translucent lacquer. Pine, bamboo, and plum tree and bush warbler designs have also been applied. Between the bush warbler and the plum tree are glyphs reading “hatsune.” Other glyphs reading “kika” and “seyo” also decorate it. The combination of the designs and the glyphs creates an uta-e, a painting that alludes to a poem. In this case, it is a poem from the “Hatsune” (First Warbler) chapter of the Tale of Genji: “Toshitsuki o matsu ni hikarete furu hito ni/kyo uguisu no hatsune kikaseyo” (For the sake of the one who has pined away these many months and years, today let her hear the first song of the bush warbler).

(Displayed at exhibitions in the temple’s Matsugaoka Museum. For details, please check the Tokeiji website.)

minutes-walk

minutes-walk

This Christian object is beautifully decorated in mother-of-pearl.

A pyx is a small box used to carry the host in the Christian rite of communion. This sacred object could be held only by the priest. The center of the lid of this pyx has the letters IHS, the symbol of the Jesuits, a Roman Catholic order founded in the sixteenth century. (IHS is a christogram formed from the first three letters of “Ihsous,” the Latin version of the Greek spelling of “Jesus.”) The sides of the pyx are decorated with a grapevine motif in the exotic Nanban (Southern Barbarian) style. Why was this object, with its Christian associations, preserved at Tokeiji, a temple with ties to the Tokugawa clan, after the Tokugawa outlawed Christianity in Japan in the Edo period? That remains a mystery.

(Displayed at exhibitions in the temple’s Matsugaoka Museum. For details, please check the Tokeiji website.)

minutes-walk

minutes-walk

A harmony of tranquility and motion

This inkstone case has a distinctive design that achieves a brilliant harmony between the hexagonal motifs, a traditional auspicious design, and an energetic wave motif. The centers of the hexagons bear a crest consisting of three horizontal lines within a circle. The hexagons and the designs on the interior of the case were created using the taka maki-e or raised sprinkled picture technique in which lacquer is used to build up the motif before applying the powdered gold.

(Displayed at exhibitions in the temple’s Matsugaoka Museum. For details, please check the Tokeiji website.)

minutes-walk

minutes-walk

An elegant nun’s implement

This brush is a special tool used by Zen priests and nuns. Originally it was used in India to brush away insects and dust. In Japan, however, Zen priests and nuns use it to symbolically expel desires. The brush part of this one is made of the hair from a yak’s tail. The handle has a Japanese arabesque design in gold maki-e on black lacquer. Its end is fitted with an ivory floret. With its unobtrusive decoration, this brush feels just right for a nun to use.

minutes-walk

minutes-walk

The Kakekomi History Lives On.

In the past, Tokeiji was a kakekomi-dera, a temple where women seeking a divorce could take refuge. Of the many documents concerning those women, this journal is especially important because it gives the date on which each woman sought refuge, the names of her parents and husband, the magistrate’s investigation—all the steps from her entering the temple to returning, divorced, to the outside world. As the “Tokeiji Document,” it was designated an Important Cultural Property in 2001. It is currently being restored.

3minutes-walk

3minutes-walk

The artist Moriya Tadashi was born in the city of Ogaki, Gifu Prefecture, in 1912. At the age of 18, he moved to Tokyo and was accepted as a student by the Nihonga artist Maeda Seison. When Seison moved to Kita-Kamakura in 1939, Tadashi followed him, moving here in 1940. The two, still Kita-Kamakura residents, received the commission for Clouds and Dragon, began work under Seison’s direction in 1962, and completed it in February of 1963.

10minutes-walk

10minutes-walk

The dragon has been long believed to be a deity that calls to the clouds and brings rain. Since the Hatto or Dharma Hall is where the dharma, the Buddhist teachings, are taught, the Clouds and Dragon painted on its ceiling signifies that it will cause the teachings to rain down.

This ceiling painting was created by Koizumi Junsaku, a Nihonga artist who was born in Kamakura, to commemorate the 750th anniversary of the founding of Kenchoji. To produce it, Junsaku borrowed the large reception room in the Hojo, a building that was originally the head priest’s residence, to use as his studio. He worked on the painting for about three years, from conception to completion. In depicting the dragon inside a circle, Junsaku’s intention was that the dragon would not be able to break out and act wildly.

16minutes-walk

16minutes-walk

Search by themes

Search by areas

- Kita-Kamakura Station area

- Kamakura Station area

- Yuigahama Station area

- Hase Station area

- Gokurakuji Station area